Cet article est également disponible en: French

Early last June [2017] 838 sheep went up to their estive (summer pastures) near Mont Rouch as they do every year. But, despite the presence of a shepherd living with them on the mountain, nearly half of them didn’t return. The reason? Bears.

A few days ago, I went to see Gisèle Gouazé, the president of the farmers’ cooperative that runs the estive, to ask her what happened. I had previously met her at a farmers’ protest meeting organised by the local council last December. This time I went to her farm in Betchat. I found her in a meadow, with two dogs at her feet, watching the sheep peacefully grazing. She was standing there with two hands resting on the end of her long stick, her feet slightly apart: a classic shepherd pose, like a tripod.

It was a chocolate-box scene: blue sky, green grass, and snow-capped mountains in the background. We talked for two hours, pleasantly warmed by the sun, accompanied by the tinkling of the sheep’s bells and their occasional quiet bleating. But don’t get the wrong impression! These sheep are the ones that survived the massacre, and Gisèle isn’t someone to mince her words.

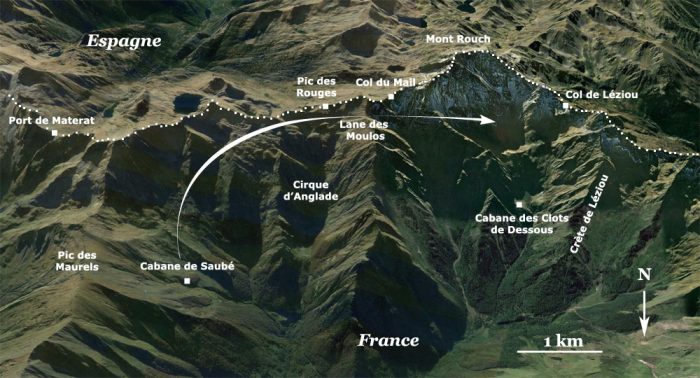

Mont Rouch estive. The arrow indicates the direction taken by the flock as in climbs up the mountain

One version of the story begins on 18 July 2017. “The shepherd didn’t understand,” Gisèle tells me, “but he sensed something was wrong.” As usual he had ‘released’ the sheep on 14 July from the Cirque d’Anglade, letting them make their own way west towards Léziou. “It takes them a week to get there. They do it themselves. They know. They sweep across the mountain.” This knowledge of the hills is passed from ewe to lamb. As James Rebanks, Britain’s Twitter-savvy shepherd (@herdyshepherd1) would say, they are ‘hefted’. But this time, after four days, they came back again.

There is another version of the story, which begins much earlier. The first pastoralists were already bringing their sheep to the Pyrenees in the Neolithic. The lower slopes were still covered in forest, as was the plain. As for the bears, they were everywhere, on the plain and in the mountains.

Or I could start the story in 1996, when only five bears remained in the Pyrenees. That was the year of the first reintroductions, from Slovenia. There are now around forty bears in the Pyrenees, most of them in one small area of Ariège: Couserans.

Let’s get back to Mont Rouch, in the high Couserans. On that morning, 18 July, the shepherd set out from the Cirque d’Anglade aiming to catch up with the flock and encourage the stragglers in their progress towards Léziou. “It was a fine day and the shepherd was doing his usual round. Then he realised that something was wrong. In the time it took to telephone us to say he had a problem [mobiles don’t work there] and for us to arrive, we had already been told that a whole flock of sheep had fallen from a cliff. My Spanish friend had rung me. A walker had seen vultures.” Vultures tearing at carcasses at the bottom of a precipice, near the Pic des Rouges.

Gisèle and the other owners climbed up, accompanied by officials, and started counting. Two hundred and nine dead sheep. Camera crews arrived to cover the event, which went on to hit the main news programmes. The footage shows the faces of the owners: shocked, sad, stunned.

But when everyone else had gone home, for the farmers there was still another mystery to be resolved. Why were the sheep coming back from Léziou?

“Afterwards, we had bad weather continuously for two weeks. We couldn’t go up there because we couldn’t see anything. At the end of the fortnight we climbed up via Léziou and we found the sheep that had fallen there [at the Col de Léziou]”

In fact, that was where the tale had really started. When the first sheep arrived at Léziou, their destination, they found themselves face to face with a bear. In their flight twenty sheep and two lambs fell off a cliff and died. The others turned back. Which explains the shepherd’s surprise.

And it was because sheep instinctively stick together when attacked that there were 209 deaths later. Normally, when sheep are left to themselves they will spread out in groups of up to fifty over an area of an acre or more. But in this case, terrorised, they clung together with predictable consequences when the bear came after them again.

Later on, the farmers would discover other carcasses. At the end of the season, in addition to the sheep killed in the attacks, 120 sheep were still missing. They could be anywhere. Dead? Lost?

“What exactly does animal welfare mean in the mountains now?” Gisèle wonders.

And it isn’t just animals that are in danger. She is also concerned about shepherds. “Our shepherds are obliged to confront these bears… We ask them to sign a thick risk assessment folder.” She holds her thumb and index finger an inch apart. “There is one line on predators… We don’t want our employees to have to cope with predators.” The Mont Rouch shepherd cannot carry a gun to defend himself because the area is within the Ariège-Pyrenees Regional Nature Park. Down on the plain the authorities are doing everything they can to reduce the risk of accidents: banning drink-driving, reducing speed limits. Why in the mountains does it work differently, Gisèle has asked the Prefect?

***

Gisèle’s is one of the six farms that come together to manage the Mont Rouch pastures. She now runs the farm with two of her grown-up children following the death of her husband François Martres in 2015. Way back in the 1970s François had returned to the village where his grandparents had lived to set up the flock, here in Betchat. And now all his work, all the work of the other farmers, is being called into question.

Among the problems for French sheep farmers: New Zealand leg of lamb, 7.75€/kg; French leg of lamb, 15.40€jan

Every year, the sheep and cattle from the six farms are driven up to the pastures around the Cabane de Saubé at the beginning of June. The cows will stay there the whole summer, but the sheep will climb higher as the snows melt.

As usual, in 2017 they explored the estive, as far as the Léziou ridge, a natural barrier which separates them from the neighbour’s flocks. The shepherd lives either in the Cabane de Saubé or in the hut at the Clots de Dessous. Every day, Gisèle tells me: “He goes up to look at the sheep, to organise them, and if one needs treating he will deal with it. If he can catch it with the help of his dog, he will do so. That’s the way it’s done around here.”

“So they are spread out over an area of three kilometres in one direction by two in the other?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“How can he find them if they need tending to?”

“Every day it’s like a pilgrimage. He does a lot of walking. On pastures like that they walk miles.”

***

“What do you think of the authorities’ reactions?” I ask.

“In Ariège, the authorities have supported us… But, well, it is always the same thing. There are rules and they can’t be broken. Even though the Ariège Prefect tries to help us as best she can, that’s the crunch. Above all it is our future that is at stake, the future of farmers who bring their flocks into the mountains each summer. The situation in Ariège is dramatic because of the concentration of bears, particularly in the Couserans.”

When I ask her if the cooperative is going to change its methods for the summer of 2018, she says that they are working on it with the Prefect, the Ministry of Agriculture and the council of Salau, the village from which they rent the pastures. The council has already asked for grants to improve the area, for installing sheepfolds, for renovating some huts and for constructing two new ones between Saubé and Léziou. The farmers have not ruled out the idea of herding the sheep into folds at night and using patous (guard dogs) to protect them.

But Gisèle is far from convinced that these officially recommended measures are effective. In addition, it would mean that the cooperative would have to completely change its way of working.

“When it’s hot a sheep doesn’t graze. She will wait until the evening, and with this system we will have to shut them in. They are likely to lose weight rather than putting it on… If we have bad weather for a fortnight we can’t just release them and bring them back again. The slopes are too steep. Or else we would have to have fewer sheep. And we still wouldn’t be safe from a disaster. We are in a tough situation. Very tough.”

Talking to her I notice one phrase which returns again and again: “C’est grave – The situation is serious.”

[…] I had talked to Gisèle Gouazé, president of the cooperative that lost the 209 sheep last […]