For anyone interested in the cultural side of rewilding, I can recommend Michel Pastoureau’s excellent book.[1] It charts the Western European perception of bears from the earliest records to the present. A renowned French historian, Pastoureau has written on heraldry, animals and, notably, on colours. But the strength of his book on bears is its focus on the how the animal fell from grace.

His thesis is that when the Christian Church started to expand into northern Europe, it found itself confronted with powerful pagan bear cults. The elimination of the cults took nearly a millennium, culminating in the 13th century when the king of the forest was symbolically replaced by the king of the jungle: the lion.

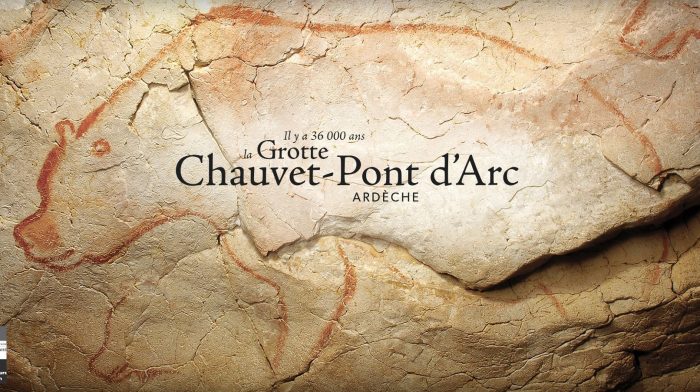

Bears have a long cultural history in France, as elsewhere. They first appeared on the walls of the Chauvet cave in Ardèche, sumptuous drawings over 30,000 years old, along with rhinoceroses, mammoths, lions, panthers and more. These were cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) now long extinct.

By the time we arrive at Classical Antiquity the bear in question is brown (Ursus arctos arctos). In Greek mythology, the goddess Artemis turns the beautiful nymph Callisto into a female bear. Meanwhile, Callisto’s new-born son remains human. After growing up to become the king of Arcadia the son goes hunting and is about to kill his bear-mother. Zeus intervenes, transforming them into the constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the Great and Little Bear.

The significance of the story is that it illustrates one of the three mythological themes associating humans and bears: metamorphosis. The second theme is a female bear that cares for a human child, and the third revolves around sex.

The similarity between bears and humans isn’t just mythological. One ecologist recently told me of a friend’s experience:

“A bear had been killed and this bloke arrived when it had just been skinned. He said, ‘When I came in, I thought it was a man lying there.’ He felt sick. That changes everything in the human–animal relationship. In popular culture – even if we are distancing ourselves from it nowadays – we are the product of that. In the past, in the Pyrenees, it was said that the bear was our ancestor… Once you have understood that, everything else seems insignificant.”

Putting ancestor legends aside for the moment and going back to Classical Antiquity, by the time of the Roman Empire, the other large animals had long since disappeared from the forests of Europe. Bears had climbed to the highest rung of the trophic ladder. A Caledonian bear features in the inaugural games of the Coliseum in 80 CE. There were even traders who specialised in circus bears. Three centuries later, killing a bear or a wild boar single-handed was a rite of purification for young men living in the lower Danube valley. But the expansion of the Empire also brought new rivals with it. Amphitheatres might host fights between a bear and a lion, a panther, or a rhinoceros.

After the Empire collapsed, although lions were waiting in the circus wings on the shores of the Mediterranean, in northern Europe it was bears that commanded respect. He who killed a bear with his bare hands was destined for great things, like the legendary Skiolduis (Skjöldr) who went on to found a Scandinavian dynasty. Many names and place names recall bears: Bern, Borm, Per, Björn… not to mention Arthur. And, for royalty, not only should one’s family tree have a bear hugging the trunk, but also one’s private zoo should have a living example.

On the other hand, for some peoples and especially for hunters, the bear should not be mentioned by name: witness the circumlocutions still used in the Pyrenees: pé descaous (the barefoot one), lo mossu (the gentleman).

Bears were powerful, not just ordinary animals: they were revered. This disturbed the nascent Christian Church, so saints were enlisted to conquer them: Florent de Saumur made a bear look after his sheep. What a humiliation! One of the miracles of St Martin – who had four thousand churches in France dedicated to him – was to tame a bear. The animal, having killed a donkey, was forced to carry the saint’s baggage to Rome. (Martin is yet another nickname used for bears.)

Part of the Church’s effort was concentrated in eradicating bear festivals. The date that bears traditionally came out of hibernation, 2 February, became Candlemas. In this New World Order this would become the day when Christ was presented at the temple. We don’t know the nature of the pre-Christian bear festivals but some of the traditions celebrated on or around that date may have old roots. One of these was the annual expedition undertaken in Ariège to hear the bear fart. Symbolically this released the souls of the dead stored underground during the winter. (More prosaically it ejected an intestinal plug due to hibernation.) Another claimed that this was the date when bears would look at the sky and decide if winter was finished (a tradition replicated in the American Groundhog Day). And a third tradition was a fertility rite.

As far as the Church was concerned, this last rite was the most dangerous. There were multiple variants, but the action revolved around a ‘bear’ abducting a young maiden who would need to be rescued by hunters. The bear would be killed, but once it was skinned the man inside would be revealed. Despite the disapproval of the Church, scores of Pyrenean villages continued to celebrate the rite until the end of the 19th century and a few, like Prats-de-Mollo, Arles-sur-Tech and St-Laurent-de-Cerdans still do so today.

In real life, sometimes a bear might succeed in his intentions. If a child was born, the Church agreed – after some debate – it could be baptised. The widely known folk tale Jean l’ours, which centres on the adventures of a young man, the fruit of the union of a woman and a bear, is part of this tradition. (It is notable that female bears, though reputedly lusty to the point of abandoning their new-born cubs to go in search of a mate, never carried off men.)

Evidently, for the Church a bear could not be the king of the animals. But who could replace him? Saint Augustine liked neither bears nor lions but in the heraldry of the Middle Ages it was the lion that triumphed – in France from the middle of the 12th century. In the various versions of the Roman de Renart, compiled around that time, Brun the bear was seen to be stupid, ridiculous and often humiliated by the wily fox. His strength and courage were no longer significant. His only good quality was being faithful to Noble, the lion-king. The bears in illuminated texts after that date were almost always portrayed with a collar, a muzzle and a chain. By the time Gaston Fébus’ book on hunting was written, around 1388, bears were considered ‘fairly ordinary animals’.

It wasn’t until the start of the 20th century that bears started to make their cultural comeback, with the arrival of the famous teddy bear. Most accounts link the invention of the new toy with the refusal of President Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt to shoot a bear cub that had been attached to a tree. An American manufacturer leapt at the opportunity to create a ‘Teddy’ ready for Christmas 1902. But Pastoureau points out that a German woman started manufacturing toy bears at the same time, inspired not by Roosevelt but by her own nephew. Whether the teddy bear was invented by a German or an American is of little importance. The significance is that the market was ready for this kind of a toy. Bears, no longer a threat, had become suitable for the nursery.

And what a revenge it was for bears! Baloo was already winning hearts and minds. Winnie the Pooh, Rupert, Paddington and others followed. But in the grown-up world of dead sheep, the real bears were not treasured bedfellows. They had long since been eradicated on the plain but there were still about a hundred in the Pyrenees at the time Rudyard Kipling was writing Jungle Book. Over the next century even that relic population dwindled.

By 1986 a French mail order company was sponsoring pro-bear associations. It co-organised an exhibition in the Paris Natural History Museum. Visiting on 6 October 1988, President Mitterrand said:

“In 1982, I made an appeal to save the bear… I reiterate it.”

Too little, too late. By 1995 there were only five bears in the Pyrenees. Although there are still some here in 2019, there are no Pyrenean bears any more. All the specimens now have a large part of Slovenian blood in them, following the reintroductions which began in 1996. Despite the government’s efforts since then, this new population is still not sustainable and greatly contested.

Rewilding is seeking to change cultural values in the grown-up world of dead sheep. For many of those shepherds living in the Pyrenees today, this new narrative remains illegible. For them, the return of bears is an attack on ancient cultural values. Who owns the mountains, they ask?

This is the subject of my forthcoming book, The implausible rewilding of the Pyrenees: notes for Britain.

[1] Michel Pastoureau: The bear: history of a fallen king (L’ours : histoire d’un roi déchu) (Harvard 2011)

Footprints on the mountains