Cet article est également disponible en: French

Don’t miss the exhibition about the Pyrenean ibex in the château de Seix (Ariège), 1 July to 31 August, 14h30 to 19j00.

Five-year-old male ibex with tracking collar, recently released in the Ariège department © Jordi Estèbe, Parc naturel régional des Pyrénées Ariégeoises

Strange things have been happening in the central Pyrenees, in a triangle bounded by Cauterets and Ustou (Ariège) on the French side and Torla (Huesca) on the Spanish side. The Pyrenean ibex has come back from the tomb.

The Pyrenean ibex (bucardo in Spanish, bouquetin in French, steinbock in German) was first reported extinct in 1825 but it actually survived until 6 January 2000, to become the first extinction of in the 21st century. Despite that, another Pyrenean ibex was born in 2009 and there are now thirty grazing in the French Pyrenees. What happened?

The Pyrenean ibex (bucardo in Spanish, bouquetin in French, steinbock in German) was first reported extinct in 1825 but it actually survived until 6 January 2000, to become the first extinction of in the 21st century. Despite that, another Pyrenean ibex was born in 2009 and there are now thirty grazing in the French Pyrenees. What happened?

The three horsemen of the ibex apocalypse were hunting, inbreeding and loss of habitat.

Hunting

For the last two centuries the few remaining ibex were concentrated in or around the Ordesa valley, near Torla. Nowadays, Torla is easily accessible from the rest of Spain to the south, but only mountain walkers still come over the watershed from France. In the 19th century it was the other way round and a surprising proportion of the hunters came from the north,[i] their journey facilitated by the opening of the railway line to Luchon in 1873. British hunters like Sir Victor Brooke wrote about their exploits, though other nationalities also competed for the prized horns.

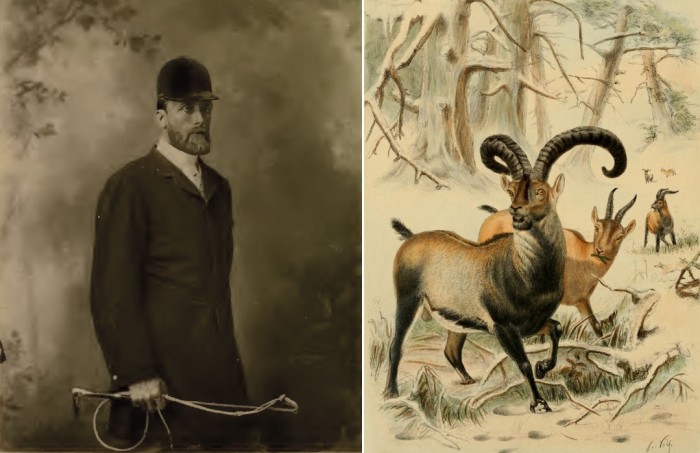

Left: Sir Victor Brooke, 1885 lived in Pau just north of the Pyrenees

Right: Plate 22 (Spanish Tur) from Richard Lydecker (1898) Wild oxen, sheep and goats of all lands, living and extinct. Based on a sketch by Joseph Wolf in the possession of Lady Brooke.

See also the original books: Sir Victor Brook, sportsman and naturalist and Wild oxen, sheep and goats of all lands, living and extinct

As a result, by 1910 when Russian prince Teodoro de Tchihatchef came hunting for ibex in the Ordesa valley – but only with his eyes – he was disappointed. After two weeks he was about to leave when local guides persuaded him to stay for just one more day. Miracle! For the first time, when he scanned the cliffs with his binoculars, he saw an ibex: on the Faja de Pelay, over a kilometre away. He insisted on going to look. Naturally, by the time he arrived the animal had disappeared, even though it was stuffed. But the prince was so happy that he engaged the guides for another two weeks.[ii]

In 1918 the creation of the Ordesa National Park made hunting illegal but it continued to a lesser extent. During and after the Spanish Civil War the soldiers and the maquis were present. They were hungry and armed and shot whatever came into their sights.[iii]

Conservation was not the spirit of the age, as one anecdote demonstrates: in a single day hunters from the American airbase in Saragossa armed with machine guns killed 30 or 40 sarrios (Pyrenean chamois).[iv] Those ibex misguided enough to stray beyond the Park’s boundaries were “intensely persecuted”.

Inbreeding

By the beginning of the 20th century there may have been only 8–9 ibex (estimate by Angel Cabrera, writing in 1914)[v] though this seems a very low figure. The highest estimate thereafter was 30, at the surprisingly late date of 1980. But by then the damage was done. Studies of the DNA of the last ibex showed a high degree of inbreeding.

Loss of habitat

The few remaining Pyrenean ibex were holed up in a restricted area. The Ordesa National Park should have given their habitat a measure of protection, but the inaugural speech gives a clue to the subsequent failure:

“It is really unfortunate that from 15 July to 15 September, which is the tourist season in the region, the French frontier of our National Park is full of tourists and constantly visited by motorists coming to contemplate Gavarnie, whilst only enthusiasts who dare defy the problems of an excruciatingly difficult voyage reach the Ordesa Valley.”

The result was new roads and an increasing number of visitors. There was even a plan to build a hydroelectric dam in the valley in 1919. Thankfully the inhabitants of Torla did manage to fight off the idea.[vi]

Even without the dam, the ibex population continued to decline.

The reincarnation

A plan to mate the last three survivors – all female – with males from outside failed because of their poor health. Although two of them became pregnant there were no live births until after the last of them, Laña, was dead.

It was in 2003. The baby ibex only survived a few minutes because she couldn’t breathe properly. She had been cloned from cells taken from Laña: a first for an extinct species.[vii] But even if she had survived, she would have had to contend with a poor genetic heritage.

Previously there had been two more conventional attempts to strengthen the population. In 1970, the Marques de Urquillo, owner of the nearby Panticosa spa, brought between 8 and 12 ibex from Gredos, where they were – and are – still surviving, and later on there was another private collection in the Sierra de Guara. They were kept in large enclosures, but most escaped before anybody really had the time to consider the implications of them breeding with another sub-species.

There were several French projects which came to nothing, until now…

This year has seen the reintroduction of ibex from central Spain into the Pyrenees. Twelve near Cauterets and twenty-one near Ustou in the Ariège, with more to come. The Parc national des Pyrénées and the Parc naturel régional des Pyrénées ariègeoises issue regular bulletins.

Three-year-old male ibex with tracking collar, released in 2014 in the Cirque de Cagateille, Ariège © Jordi Estèbe, Parc naturel régional des Pyrénées Ariégeoises

The Pyrenean ibex is dead. Long live the (Pyrenean) ibex.

In this land of the living dead, the other zombies are the bears…

Sources

- Kees Woutersen (2012) El bucardo de los Pirineos, Kees Woutersen Publicaciones, Huesca, see also http://www.bucardo.es/

- The sixth extinction

- Pyrénées Magazine had a feature article on the Pyrenean ibex in its November/December 2014 edition.

Footprints on the mountains